We hear “don’t judge” everywhere in our society: on social media posts, in classrooms, in artwork. Even in most Christian circles, the word judgment is treated like a sin.

This entire concept is often misunderstood, and reduced to a misquote of Christ’s words in the Gospels: ‘Judge not, lest ye be judged.’

This modern misunderstanding lies in equating judgment with mere criticism or disagreement. Yet Scripture does not forbid judgment.

What it forbids is condemnation.

In biblical Greek, two different words are often translated as “judge”:

• κρίνω (krinō) – to discern, separate, or evaluate.

• κατακρίνω (katakrinō) – to condemn or declare damned.

Jesus warns against katakrinō: the arrogant presumption that someone is beyond saving, that we can play God and declare a soul lost. That kind of judgment is indeed forbidden.

But krinō? That’s the kind of judgment the Bible commands us to partake in:

“Do not judge by appearances, but judge with right judgment.” (John 7:24)

“The spiritual man judges all things.” (1 Corinthians 2:15)

“Or do you not know that the saints will judge the world? And if the world is to be judged by you, are you incompetent to try trivial cases? Do you not know that we are to judge angels? How much more, then, matters pertaining to this life!” (1 Corinthians 6:2–3, ESV)

To judge rightly is to see rightly: to discern truth from error, good from evil, the wise path from the foolish one. Without this kind of judgment, the Christian life collapses. It loses its direction, and ultimately, its meaning.

How can we pursue virtue, protect the innocent, or love rightly if we no longer know the difference between what is right and what is wrong?

Yet even this true form of judgment has been darkened in modern culture. We’ve confused reasoned discernment with personal condemnation. In doing so, we’ve lost our moral compass. And worse, when we try to judge rightly, we often no longer know how.

This is the fruit of moral relativism.

Moral relativism claims that right and wrong depend on personal opinion or cultural norms, and that no universal moral truth exists. But this view is false. It denies the natural law, which teaches that certain moral truths are objective, rooted in human nature, and binding on all people at all times.

When we abandon natural law, we lose the ability to call anything truly good or truly evil. The result is confusion, injustice, and spiritual blindness.

Long before modern psychology, long before social media blurred every moral line, the Church Fathers and the scholastics knew that judgment itself had to be purified.

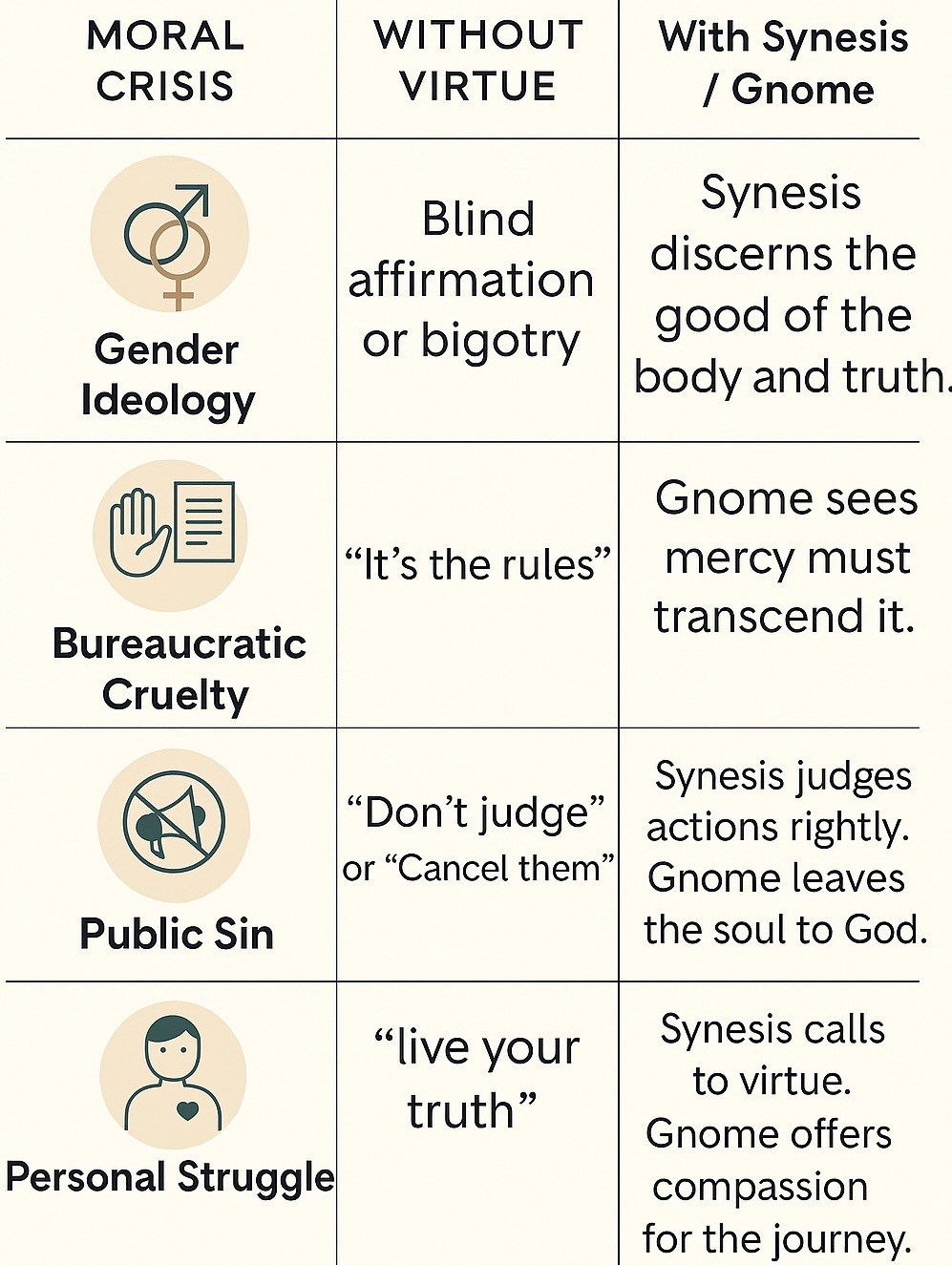

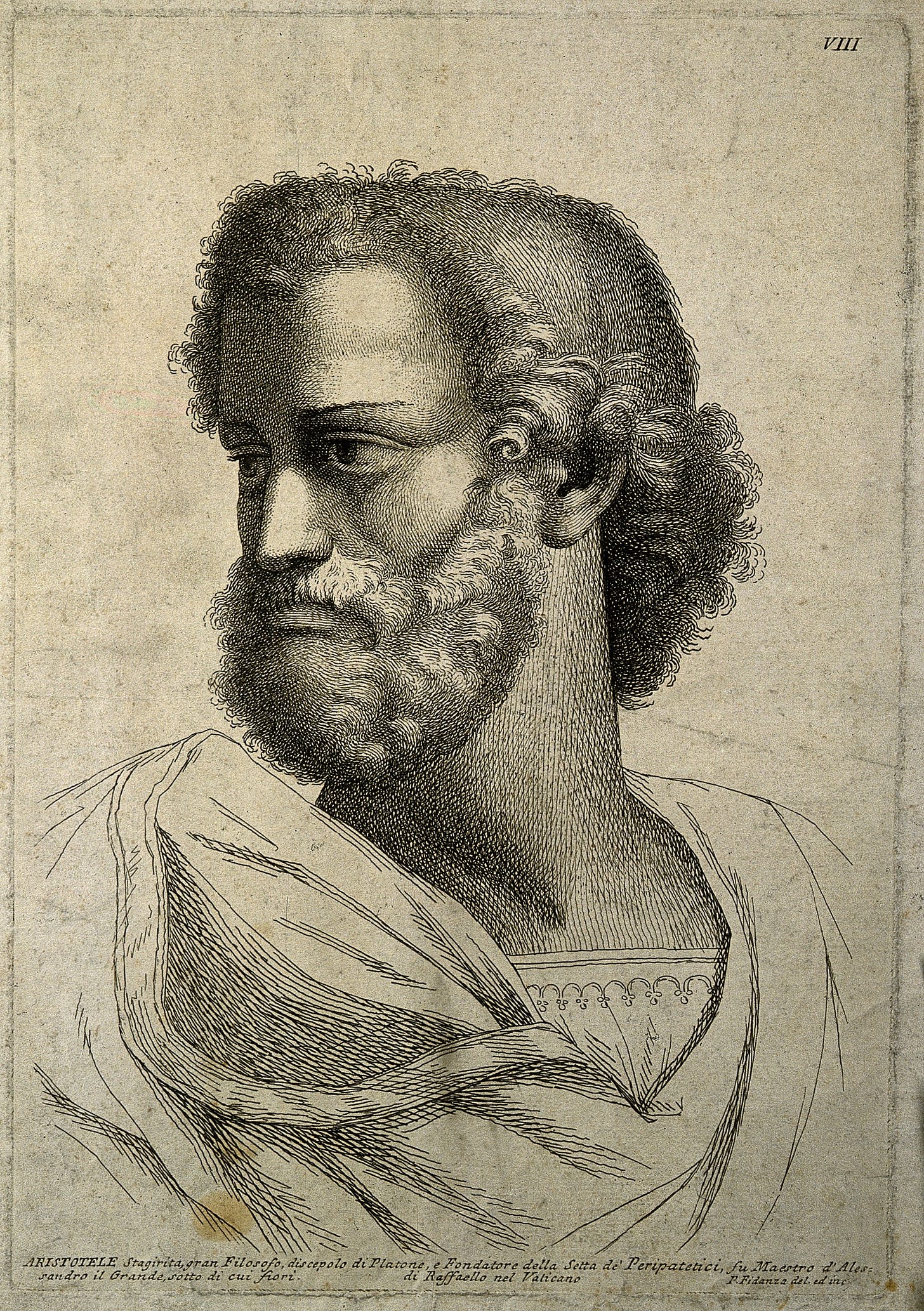

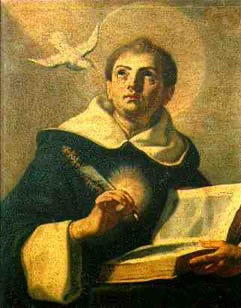

Saint Thomas Aquinas, drawing on the wisdom of Aristotle and the Gospel, taught that prudent action requires right judgment, and right judgment depends on these two often-forgotten virtues:

• Synesis: sound judgment in ordinary situations, guided by moral law and reason.

• Gnome: elevated judgment in exceptional cases, guided by deeper principles and divine charity.

These are not mere intellectual gifts. They are moral muscles formed by virtue, refined by grace, and absolutely necessary for living the Christian life with clarity and courage.

What happens when a culture loses synesis and gnome?

It confuses love with indulgence.

It substitutes feelings for wisdom.

It punishes the just and affirms the wicked.

In short: it cannot judge rightly, because it no longer sees clearly.

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see this happening everywhere around our world, but how can we fix it?

The solution is not more education, louder arguments, protests, or stricter laws, despite what politicians would have us believe. What we need is formation. The restoration of moral vision through the cultivation of virtue.

These virtues restore what sin destroys: our ability to see the world as God sees it. Without them, even the well-intentioned become blind guides for spiritual decay.

The Eyes of Prudence

Aquinas defines prudence as right reason applied to action, a virtue that governs the entire moral life. But prudence does not act alone. Before it can command what ought to be done, it must first see and judge.

That’s where synesis and gnome come in.

These two virtues, drawn from Aristotle and perfected by Christian revelation, are what Aquinas calls “integral parts” of prudence’s judgment:

• Synesis judges rightly in ordinary matters, using moral laws and established norms.

• Gnome judges rightly in extraordinary cases, using higher moral insight when the law doesn’t clearly apply.

Synesis allows us to judge rightly in the ordinary:

How to treat a co-worker.

How to raise a child.

How to navigate temptation.

Gnome elevates us to judge in the extraordinary. When the moral path is not found in the letter of the law but in the higher law of divine wisdom.

Together, they give prudence its vision. They are the eyes that allow moral reason to distinguish the path of virtue from the path of error.

Aquinas, echoing Aristotle, says:

“Such as a man is, so does the end seem to him.”

The good man sees what is good more clearly than the wicked man ever can.

Unfortunately, the concept of Synesis has vanished from public discourse. In its absence, we find a culture afraid to say “this is wrong,” silenced by the fear of offending. What was once morally clear has been turned upside down. Lust is called love. Discipline is labeled cruelty. Authority is treated as oppression.

Examples:

• A parent lets the child dictate the moral tone of the household instead of forming them with wisdom and love.

• A Christian avoids speaking about sin under their jurisdiction out of fear of sounding judgmental.

• A politician lies to the public and justifies it as being for “the greater good.”

But synesis is not extinct.

It still lives in places the world rarely notices.

It lives in the quiet grandmother who knows that patience is better than yelling, but correction is better than neglect.

It lives in the teacher who walks the narrow line between compassion and discipline, who refuses to flatter her students or abandon what is right.

It lives in the priest who proclaims the fullness of the faith, even when it costs him popularity or donations, because he knows that charity without truth is a lie.

In the old man at the grocery store who speaks little, yet radiates the peace of a soul conformed to something eternal.

These are not grand or heroic moments in the world’s eyes. They are the quiet tensions of daily life. And it is precisely here (in the ordinary) that right judgment is most needed. Not to discern the exceptional, but to see clearly in what is common.

That is the lost art. And it must be found again.

Gnome: The Higher Discernment for Difficult Cases

If synesis is judgment in the normal, gnome is judgment in the rare and difficult.

Gnome is the ability to judge rightly when the ordinary rule cannot be applied without causing injustice. It discerns when the spirit of the law must be followed rather than its letter.

Aquinas says that gnome judges by “higher law”, not in the sense of human hierarchy, but in the sense of divine order. It is the moral intuition of the saint who knows when charity must guide the soul beyond the written code.

Examples from Today’s Terms:

• A soldier temporarily entrusted with a weapon refuses to return it to a man intent on murder.

• A nurse in a war zone breaks hospital policy to save a child’s life.

• A teacher shields a student from abusive parents, even though protocol says “report and release.”

• A man defends his family against a corrupt official who hides behind “legal authority.”

Gnome is what saves justice from becoming cruelty.

How to Grow in Synesis and Gnome

Knowing what these virtues are is one thing. Becoming a person who possesses them is another.

It’s not enough to try to judge better. Right judgment is the result of a rightly ordered soul. Aquinas and the saints show us how these virtues are formed not by technique, but by transformation.

⸻

1. Purify the Intellect through Moral Virtue

“Such as a man is, so does the end seem to him.” – Aristotle, quoted by Aquinas (Ethics III.5)

According to Saint Thomas Aquinas, we do not see clearly unless we live rightly. The intellect does not operate in a vacuum. It is shaped, elevated, or distorted by the moral condition of the soul.

Pride twists our perception of honor.

Lust distorts the good of the body.

Fear inflates danger and shrinks courage.

Anger narrows vision to vengeance.

In short, sin darkens the intellect, making evil appear good and good appear excessive or foolish.

This is why growth in virtue: temperance to order the passions, fortitude to resist fear, justice to will rightly, and above all, charity to love as God loves, is essential to clear thinking.

Virtue purifies the will, calms the passions, and allows the intellect to regain its natural and supernatural light. Without moral virtue, there is no clarity of mind. And without clarity of mind, synesis and gnome cannot take root. Because the soul that cannot love rightly cannot see rightly either.

⸻

2. Form the Habit of Prudence

Prudence is the virtue that commands right action. But it cannot exist without right judgment.

According to Saint Thomas Aquinas, prudence grows through the cultivation of specific habits in the soul.

These include memory, which draws wisdom from the past; docility, which keeps the mind teachable; circumspection, which discerns the details of a situation; and caution, which foresees obstacles before they strike.

Prudence is not mere calculation. It is wisdom applied to reality. It listens to conscience, integrates reason, and directs the will toward the true good. It is the bridge between knowing what is right and doing what is right.

And when prudence matures, synesis and gnome begin to flourish.

Because these two virtues are not stand-alone gifts, they are the fruit of a soul trained in the art of seeing clearly and choosing rightly.

The more the intellect is disciplined by truth, humbled by experience, and conformed to God’s will, the more it can judge rightly: not only in theory, but in the real and messy circumstances of daily life.

That is where virtue lives. And prudence is what gives it direction.

⸻

3. Receive the Gifts of the Holy Spirit

Aquinas makes it clear: natural virtue is necessary, but it is not enough. The human intellect, while noble, is limited. Sin wounds our reason, and even the most virtuous person can struggle when faced with complexity, spiritual darkness, or exceptional moral situations. That is why divine grace must perfect what nature begins.

To guide the soul beyond the limits of human prudence, God pours out the Gifts of the Holy Spirit. These are infused dispositions that make the soul docile to divine movement. They perfect the intellect, elevate judgment, and make the Christian capable of discerning in light of God’s own wisdom.

The Gift of Counsel strengthens moral decision-making, especially in difficult or unforeseen circumstances, where no clear rule applies. It is the supernatural counterpart to synesis and gnome: infusing our judgments with divine clarity when human reasoning falls short.

The Gift of Understanding penetrates beneath the surface of the law to reveal its inner truth. It allows the soul to see the why behind the what: to perceive God’s wisdom hidden within the fabric of reality.

The Gift of Wisdom perfects the intellect even further. It enables the soul not only to know the truth, but to taste it. Wisdom orients every judgment toward the final end (which is God Himself) and harmonizes the soul with eternal things.

Without these gifts, synesis and gnome remain limited to the natural order. With them, the Christian begins to judge not only with reason, but with the mind of Christ.

This is why the saints did not merely act prudently, they judged with light from above. And that light is available to us too, if we are willing to be led by the Spirit.

⸻

4. Study the Saints, Not Just the Rules

If we want to grow in the virtues of synesis and gnome, we must look beyond abstract theories and turn to the lives of the saints. Their stories reveal how right judgment is formed not in controlled conditions, but in the unpredictable challenges of real life, as a human.

The saints teach us how to balance principle with love, and conviction with compassion. They lived in difficult times, faced imperfect authorities, navigated moral gray areas, and responded with clarity shaped by grace.

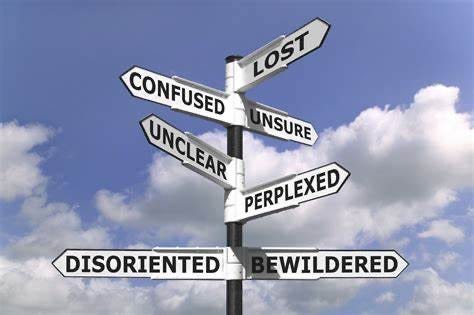

St. Anthony the Great was illiterate, yet his judgment surpassed that of the most educated men. Living in the desert, he faced temptations, heresies, and the spiritual wounds of countless visitors. His clarity came not from books but from asceticism, interior silence, and constant communion with God. He discerned when to speak and when to remain silent, when to correct and when to let grace unfold. His wisdom was pure, unclouded, and deeply rooted in the Spirit.

He warned, “A time is coming when men will go mad, and when they see someone who is not mad, they will say, ‘You are mad; you are not like us.’”   His life shows us synesis at work: in knowing when to speak with fiery admonition and when to remain utterly silent before the desert stretched on.

St. Pachomius founded the first cenobitic monastic communities. He judged wisely how to lead souls toward holiness not through harsh control, but through structure, rhythm, and communal life centered on Christ. He knew when to permit, when to correct, and when to wait. His discernment created a model of holiness that still shapes monastic life today.

St. Benedict of Nursia, in a collapsing Roman world, composed a rule that taught men how to live in harmony with God and each other. His vision of order, silence, labor, and prayer reflected profound synesis. His guidance extended to the smallest details: how to eat, when to speak, how to handle disputes. He judged everything in the light of eternity, and his rule shaped Western civilization.

Benedict also knew when the letter of the law was not enough. He wrote, “The abbot should so temper all things that the strong may still have something to yearn after, and the weak may not draw back in alarm.”

St. Isidore of Pelusium, a theologian and letter-writer, gave spiritual direction to bishops, monks, and laypeople alike. He spoke with humility, yet with force when truth was at stake. His letters often carried the weight of gnome, responding to what no written law had yet addressed.

He wrote, “It is more important to be proficient in good works than in golden‑tongued preaching”. His counsel was never empty rhetoric.

By studying their lives, we train our own ability to see clearly. We learn how to speak the truth without cruelty, how to love without compromise, how to respond when rules seem insufficient, and how to remain faithful when conscience is tested.

⸻

5. Contemplate Divine Truth

The intellect must be bathed in eternal light. Without divine illumination, the mind becomes clever but not wise, reactive but not discerning. Saint Thomas Aquinas insists that true judgment, whether synesis in the ordinary or gnome in the extraordinary, depends first and foremost on loving what is true. But we cannot love what we do not know, and we cannot know what we will not contemplate.

Scripture trains the soul to think with God. It does not merely inform us. It reforms us, cleansing the mind of worldly distortions. It sharpens conscience and expands perception, so that even simple commands echo eternal realities.

The Summa Theologiae forms moral precision. It is not dry philosophy. It is a ladder of ascent. Each article, each distinction, is a chisel that frees the intellect from confusion and false mercy. In studying what is true, the mind becomes habituated to seek God’s wisdom, not man’s opinion.

Prayer and lectio divina open the mind to grace. Prayer humbles the intellect. It says, “I do not see clearly unless You show me.” Lectio divina doesn’t treat Scripture like data, but like light. Slowly, reverently, it soaks into the soul, teaching us how to see with heaven’s logic.

Aquinas would say: right judgment is not merely a matter of intelligence. It is a matter of purity. You will never judge rightly until your heart loves what is true, and that love is forged in silence, study, and worship.

This is why truth must not only be accepted. It must be contemplated. Not skimmed or wielded to win arguments, but interiorly gazed upon until it reshapes your soul. Truth must become beautiful to you. Desirable. Worth suffering for.

You must love the truth, even when it wounds your pride or breaks your heart. Even when it means changing your life. Even when it separates you from the crowd. To will what is true regardless of the cost is to mirror Christ on the Cross, who is Truth made flesh and Love poured out.

That is true love.

That is agape.

And that is where all judgment must begin.

“Among men, he who is most discerning can judge a greater number of things that occur outside the common order: and this belongs to gnome.”

— St. Thomas Aquinas

We don’t need more cleverness.

We need vision: eyes that can see both the ordinary and the exceptional, rightly and humbly.

Synesis and gnome are not optional. They are essential. They are the forgotten framework of the moral life, and the tools by which God trains saints.

If you desire holiness, pray for them. If you desire clarity, form them. If you desire to see truly, begin here.

Thank you for reading Seeking Heaven. We’re deeply grateful for each of you who journeys with us in the pursuit of truth, beauty, and sanctity. If this article sparked something in your heart or challenged your thinking, we invite you to leave a comment, share it with a friend, or simply take a moment to reflect with us in prayer.

Below, you’ll find a reading list of sacred texts and spiritual writings that have recently shaped our team’s reflections. These works, rich in wisdom and divine clarity, are companions on the road to deeper discernment:

Life of St. Anthony the Great

Written by St. Athanasius. A powerful biography of the father of desert monasticism, rich in discernment and spiritual battle.

Sayings of the Desert Fathers

A collection of short, sharp wisdom from early monks like Anthony, Arsenius, and Macarius. Ideal for cultivating interior clarity.

The Pachomian Rule

The first monastic rule for communal life, emphasizing obedience, structure, and spiritual order.

Life of St. Pachomius

Accounts of his supernatural leadership, visions, and wise discernment in shaping early cenobitic monasticism.

The Rule of St. Benedict

A masterpiece of spiritual order. Governs everything from meals to prayer with profound moral vision and moderation.

Dialogues (Book II – St. Gregory the Great)

A miraculous account of St. Benedict’s life, showing his spiritual authority, prophecy, and wise rule.

Letters of St. Isidore of Pelusium

Over 2,000 letters offering doctrinal clarity and moral advice: balanced, pastoral, and deeply rooted in Scripture.

Praktikos (Evagrius Ponticus)

A guide to battling sinful thoughts and forming the virtues needed for spiritual vision.

Reflections on the Eight Evil Thoughts (Evagrius Ponticus)

Early treatment of what became the “seven deadly sins,” showing how sin clouds the intellect.

Conferences (St. John Cassian)

Dialogues with desert monks on purity of heart, discernment, and spiritual balance: timeless ascetic wisdom.

Institutes (St. John Cassian)

Practical teachings on monastic discipline and virtue, structured for daily transformation.

Four Hundred Chapters on Love (St. Maximus the Confessor)

A contemplative journey through divine charity and the soul’s transformation in truth.

Ambigua (St. Maximus the Confessor)

Dense, mystical theology unpacking difficult patristic texts with insight into God’s providence and human freedom.

Ascetical Homilies (St. Isaac the Syrian)

Soul-piercing meditations on silence, mercy, and divine love. Deeply contemplative and timeless.

The Ladder of Divine Ascent (St. John Climacus)

A step-by-step path to heaven through repentance, detachment, humility, and spiritual warfare.

Summa Theologiae (St. Thomas Aquinas)

The greatest theological synthesis ever written. Includes detailed treatment of prudence, justice, judgment, and virtue.

Commentary on the Nicomachean Ethics (St. Thomas Aquinas)

Aquinas’ deep engagement with Aristotle on virtue, habit, and the formation of right reason.

Compendium Theologiae (St. Thomas Aquinas)

A shorter summary of the faith, accessible and ordered, with insights on the moral life.

On the Virtues (St. Thomas Aquinas)

Explores cardinal and theological virtues in precise yet spiritually rich language.

May these saints and their words become not only inspiration, but formation. May we judge rightly, live humbly, and love well.

—The Seeking Heaven Team

This is a very helpful article, clarifying where language and translation can obscure Biblical truth, but also hugely practical steps for forming ourselves and strengthening our moral and spiritual vision and "muscles". Thank you so much!

Such a great article! We need to reflect and get stronger to have better discernment and this explains how we can start. Thank you for posting!